How To Run When You Can’t Walk: The Experience Of The L.A. Fires With A Disability

Navigating A Natural Disaster With Long Covid

Original Art By GG.

It’s All In My Head

Welcome to It’s All In My Head. I’ve been sick with Long Covid since 2020. This publication documents my experience living with a chronic illness and navigating the unknown as we learn more about the long-term effects of Covid. For context, start with these articles:

Los Angeles Magazine — It’s All In Your Head: One L.A. Woman’s Struggle With Long Covid

My interview with NPR’s All Things Considered: Long Covid: Millions Have It. Why Do We Know So Little?

You can learn more about my main publication, Only Murders In The Inbox, here.

If you’re struggling with a chronic illness or love someone who lives with a disability, this publication is for you. If you suspect you or someone you know has Long Covid, this is a space for support. Subscribe below.

If you’re a free subscriber who’s not ready to commit to a paid subscription, you can also make a one-time contribution by Buying Me A Coffee.

Your support is helping me through a difficult time in my life, so please know how much I appreciate you!

Wednesday morning, January 8th, in northeast L.A. on Figueroa when we evacuated. That thin sliver of blue is the sky.

Experiencing A Natural Disaster With Long Covid

Growing up in Florida, I’m more than acquainted with natural disasters. I’ve lived through dozens of hurricanes and tropical storms (according to FEMA, more than eighty-three!) from my childhood through college. Many of these hurricanes were life-changing ones for my home state of Florida: Hurricane Andrew, which was one of only five hurricanes to ever hit the coast of the United States as a Category Five; Hurricane Michael devastated my sister’s library and decimated my family’s favorite beach, where I spent every summer during my childhood. I’ve had trees fall through houses, flooding destroy a car, and even a close call hydroplaning on a slippery Florida highway in a tropical storm. I’d even dealt with a wildfire here in California. In a car. On the 210 freeway. Guess what? Fires can cross freeways, I know this firsthand. I’m not kidding.

But I’ve never had to evacuate. Until now.

As a healthy adult, a natural disaster can be nerve-wracking. You have to think about your partner, your kids, your pets, elderly relatives, your home and the life you’ve built. You’re juggling a million and one thoughts and fears, preparing yourself for the worst but hoping for the best. You’re scrambling to get out the door and everyone’s not moving fast enough. But when you’re healthy you’re quick, mobile, and when you need to go, you flee.

As a disabled person, it’s all together different. You don’t know fear until you realize you’re in a life or death situation and you realize you can’t hurry, you can’t run, and you can’t help yourself, let alone the people you love. Not only that, you’re entirely dependent on other people to survive. It’s terrifying.

January 8th in Los Angeles. Photo By KG.

Two weeks ago on Wednesday, our family left our home in northeast Los Angeles. We woke up at six in the morning, choking from the smoke. One of our cats was wheezing, which woke up our kids, who panicked when they looked outside and saw nothing but orange. My throat and lungs were burning. At one point, I looked over at my husband and realized his eyes were bloodshot and watering from the smoke. We threw clothes and important papers in bags as we looked out our garden window to a blood orange sun ripping through the grayest, darkest sky I’ve ever seen that wasn’t night.

Since the wildfires, the AQI in neighborhoods in Los Angeles has fluctuated in and out of very unhealthy and hazardous levels.

I’ve had pain on inhalation for years now because of Covid — but no cough — that inhalers don’t help. When our air quality number is over 50 AQI (Air Quality Index) I’m reluctant to go outside because my lungs are so damaged from Covid. By the time we left, it was 384. As we were leaving, we saw charred pages of books in our front yard, which is insane. That tells you how far the Santa Ana winds were carrying embers and ash from the Eaton Canyon fire into other parts of L.A. County.

We couldn’t fit my wheelchair in the car with all of our luggage. We have two cars but my husband thought it would be best if our family stuck together, and I agreed. Would we rent a wheelchair when we arrived? How would I get in or out of buildings? Because of chronic fatigue and POTS, I black out if I’m standing up for too long. Back when I was interviewed for NPR, my ability to stand was around ten minutes long; now I’m closer to fifteen. But I can’t walk further than a block. I can’t climb a flight of stairs without sitting down on the landing. I forgot the camping stool I use as a backup. I forgot the handicap placard for the car, too. When you’re evacuating in a true emergency with no warning, you grab your kids, your pets, your passports and your medicine — in that order — and your partner’s hand and flee. That’s it.

We drove forty miles outside the city to safety in Orange County where, the air quality was (and still is) significantly better (but not great). We watched as plumes of smoke billowed over L.A. from our hotel window and wondered if our home would still be standing once we could return. Our hotel was full of evacuees from the city, crowding the downstairs bar and lobby. Some of them were friends and people we knew.

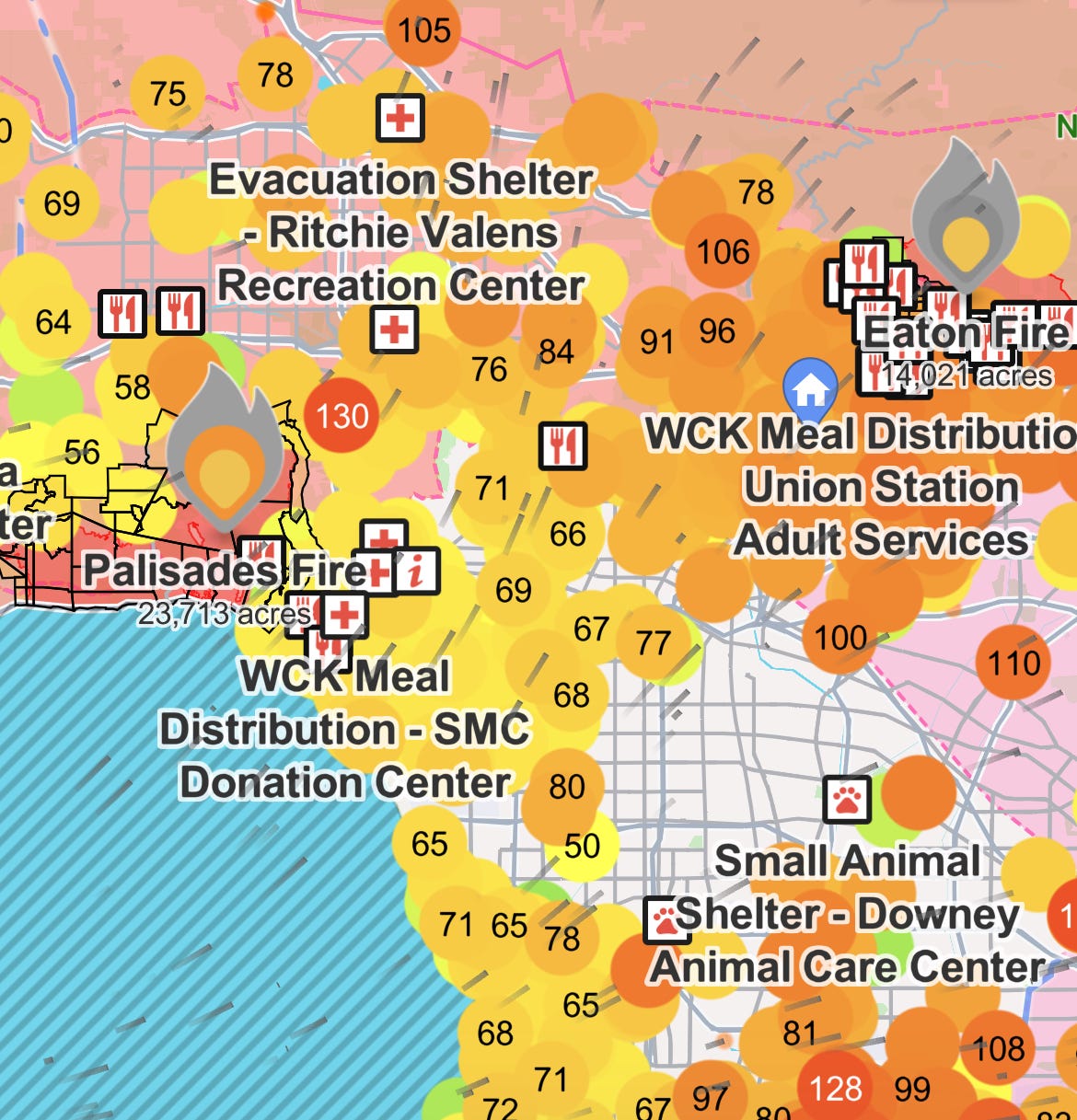

The Watch Duty map of L.A. on Sunday, January 19th. Our home is the blue house on the map.

When we evacuated, we didn’t know what it would be like with a huge portion of L.A. fleeing the fires. We felt especially fortunate that we got out when we did, because it was impossible to know how difficult it might be to get out of L.A. if the Palisades and Eaton Canyon fires continued to spread into even more densely populated areas. At the time of this writing, the fire closest to our home, the Eaton Canyon Fire, is at 14,117 acres. The Pacific Palisades Fire is at 23,713 acres. Our home is between these two fires in northeast L.A. We’re currently under a Red Flag warning because of the high winds for the next several days, some predicted to get as high as 80-100 miles per hour. Both fires are closer to being contained, but this is far from over.

Driving back to Los Angeles on Sunday, January 12th.

On January 12th, we drove home, reassured the winds had shifted and progress was being made on containing the blaze. That Wednesday morning when we evacuated we thought we’d never see our home again. The relief that overcame us when we pulled up to the house brought me to tears. It was covered in ash but still standing. The Santa Ana winds downed trees and knocked out the power, but fortunately not on our street. The wildfire left more than an inch of ashes all over our yard, coating everything, including the car we’d left behind. The swing. Our plants. A thick haze was everywhere.

We know how fortunate we are and that so many people in L.A. have lost so much. We know dozens of people, some in the Pacific Palisades but most in Altadena, who have lost everything. Our heart goes out to them, and we grieve with them.

We are extremely lucky, but that hasn’t been the end of it. Having Long Covid has complicated everything. When we returned that Sunday, the air quality was between 90-120 AQI. We have multiple air cleaners throughout our house because when one of our kids was younger she had asthma, and we’re often concerned about air quality, even more so since I’ve been sick.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports on AQI for five major air pollutants regulated by the Clean Air Act. Each of these pollutants has a national air quality standard set by the EPA to protect public health:

ground-level ozone

particle pollution (also known as particulate matter, including PM2.5 and PM10)

carbon monoxide

sulfur dioxide

nitrogen dioxide

When you’re checking the weather on your iPhone and you scroll down, that’s what the AQI number indicates: the amount of these five major pollutants. However, when there’s a wildfire, especially one that hits neighborhoods and homes, there’s more than these five pollutants in the air. There’s asbestos from older homes and buildings, lead from lead paint, tires, appliances, gas, coolants, chemicals, etc. The actual level of air pollution in L.A. right now is far, far higher than that number on your Weather app. It’s very unhealthy and, in certain areas, hazardous.

The air quality, coupled with my disability, has been far more dangerous for me than the actual fire.

I only lasted four days at our house. We’re not in Altadena; we live in a neighborhood closer to downtown about nine miles away from the center of the Eaton Fire. But that doesn’t matter. The pollution is so bad, and I am so sick, that there was no way I could stay in our home. The sharp pain in my chest like sparklers popping, my throat burning, the difficulty inhaling — I couldn’t do it. I cried. My husband put his arms around me and told me we needed to go, so we did.

So I’ve evacuated now for a second time. I’m writing this newsletter edition from my hotel. I’m with my family in Anaheim; my kids are here just for the long weekend because Los Angeles Unified School District only closed our public school for three days. Is it safe on campus with the current level of pollution? I honestly don’t know. I can’t possibly see how the answer could be yes.

I don’t know what to do. I can’t stay here forever, but I also can’t go home. There are lots of other disabled Angelenos like me. We left for our health and safety; some people couldn’t and are still there, suffering. We’re all stuck, caught in this precarious situation that has no end — not unlike my illness itself.

Angelenos, here are some resources:

California State Resources and Contact Lists

If you are evacuating and seeking shelter, text “SHELTER” and your zip code to 43362 to locate the nearest one to you.

L.A. Times: Altadena family says disabled father and son were left to burn: ‘Nobody was coming’

KTLA 5 News: Disabled Eaton Fire victim escaped deadly flames in wheelchair

I’m so sorry, my friend. If I had a place to my lonesome I’d offer it to your family.

Loved this